For six years, Carter had dug up the desert sands in the Egypt’s Valley of the Kings area in search of the tomb of the famed boy pharaoh Tutankhamun but to no avail. The Earl of Carnarvon, who financed the search had become impatient, and gave Carter one last chance.

Then, a local boy named Hussein Abd el-Rassul, who was bringing water to the workers, hit a stone step under the rubble. From then on the excavation team did not stop. They uncovered 16 steps in all and also found two seals with Tutankhamun’s royal mark. But it wasn’t until Lord Carnarvon arrived from England that Carter opened the tomb’s antechamber on November 26, 1922, and the real breakthrough happened.

“Can you see anything?” the Earl is said to have asked.”Yes, wonderful things,” Carter answered back.

The men had stumbled upon priceless treasures that no human eye had seen in more than 3,000 years.

“We had the impression of looking into the prop room of the opera of a vanished civilization,” Carter later described his first impressions. “Details from inside the chamber slowly emerged from the mist — strange animals, statues, gold. Everywhere, the glint of gold.”

For 10 years, the British archaeologist and his assistants meticulously cataloged every tomb artifact. The most important finds are now in the Egyptian Museum in Cairo and in Luxor itself.

The most famous of the approximately 5,400 objects found is still the 11-kilogram blue-gold death mask of Tutankhamun himself. Enclosed by four shrines of gilded wood, a stone sarcophagus and three mummy-shaped coffins placed one inside the other, lay the embalmed pharaoh in a 225-kilogram coffin of pure gold. The death mask covered his face.

THE START OF “EGYPTOMANIA”

Word of the sensational find spread quickly, triggering worldwide “Egyptomania.” The discovery prompted architects to create Egyptian-style facades. Jewels, handbags, clothing and even cookie jars and juice bottles bore the unmistakable symbol of the gilded king’s mask. General Motors touted a vehicle in the shape of a pharaoh.

In a New York Times February 25, 1923 article one fashion guru pronounced that America was in a better mood to produce styles than Europe due to World War I, and this year the American shows were dominated by Egyptian fashions. A February 27 article proclaimed a “complete change in furniture, decorations, jewelry and women’s dress… as a result of the discoveries in the tomb of Tutankhamun.” The newspaper also reported that Washington D.C.’s Patent office received a flood of applications for the use of Tut-Ankh-Amen as a trademark–objects chiefly for “women’s use.” In fact, commercially, Tutankhamen made the biggest impact on women’s fashion.

100 years down the road, Ancient Egypt and King Tut continue to inspire designers worldwide.

While the world was first awed by all that gold , the tomb also contained wooden chests filled with the boy king’s wardrobe of textiles and accessories that accompanied the glittering objects. These include: 145 loincloths, 12 tunics, 24 shawls, 28 pairs of gloves, 25 head coverings and 15 sashes, along with 47 pairs of shoes and four pairs of socks, plus two leopard skins and two aprons.

Textile archaeologist, Dr Gillian Vogelsang-Eastwood has spent a lifetime studying and cataloguing these impressive surviving textiles and accessories. Heading two teams of international experts, she organised the reproduction of 36 wardrobe items using ancient textile production methods. The Weaving School in Boras, Sweden produced royal linen cloth, based on the ancient originals, while the embroidery, printing and beadwork was carried out by the Stichting Textile Research Centre, Leiden.

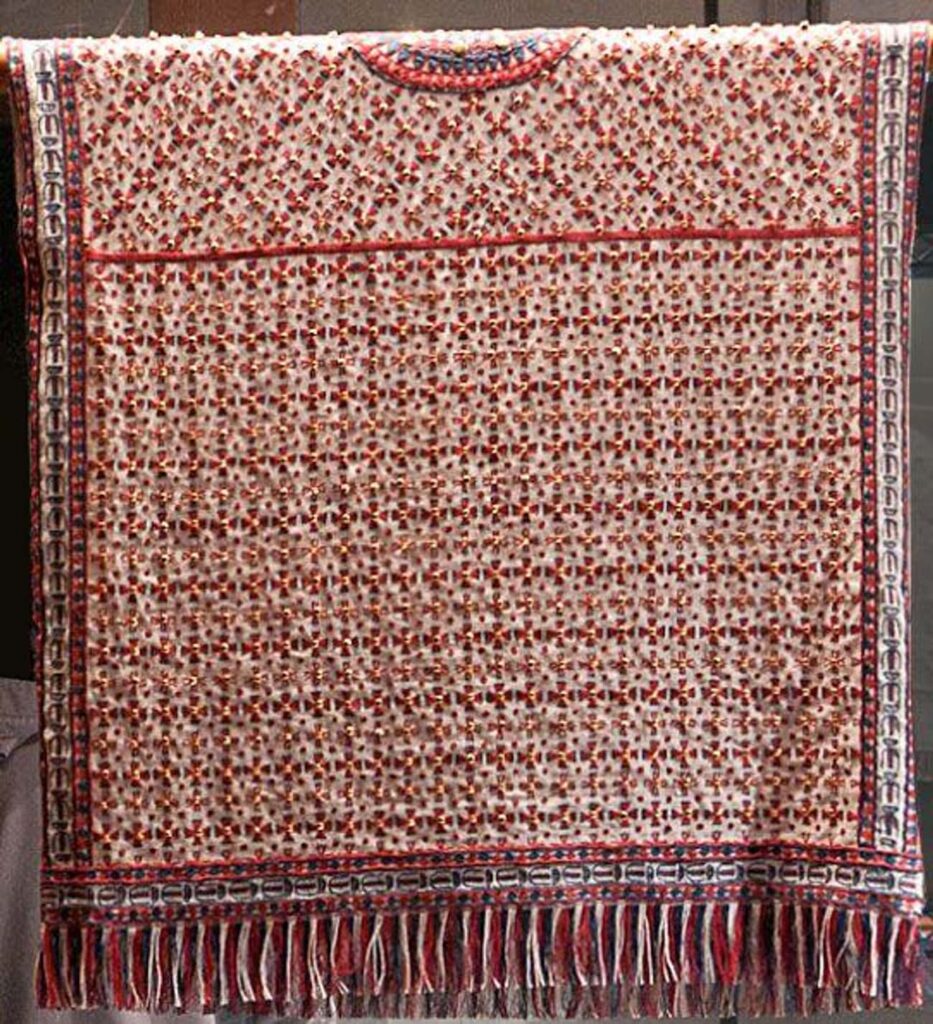

The Heb-Sed Outfit

The repeating pattern of Heb-Sed hieroglyphs, most noticeable along the trim, shows that it was made specifically for the young Tut to attend the ruling pharaoh’s jubilee celebration in Memphis, Egypt. It’s the only one of Tut’s garments that researchers can pin to a specific event, though it’s unclear which pharaoh was celebrating his Heb-Sed.

The “Syrian” Tunic

This was Tut’s only garment with sleeves, designed for him when he was an early teen. His crowning name, “Nebcheperture,” is woven in cartouches around the collar along with images of the tree of life. In order to reproduce this garment, the Borås Weaving School consulted Bedouins in Egypt who still spin thread on spindles and weave similar designs on looms that haven’t changed in 4,000 years. The “Syrian” tunic was most likely sent as a diplomatic gift from Egypt’s longtime trading partner, the Mitanni Kingdom located in modern-day Syria and Angola, where sleeves were all the rage.

The Falcon Tunic

This tunic is covered in powerful imagery. Falcon wings spread out from either side of the neck so that when Tut put this tunic on, his head became that of the sky god, transforming him into the “Living Horus.” The blue flower pattern inside the red rosettes symbolized Tut’s kingly authority and his ability to live forever like the sun god Re who was said to rise each morning with the opening of the lotus blossoms on the Nile.

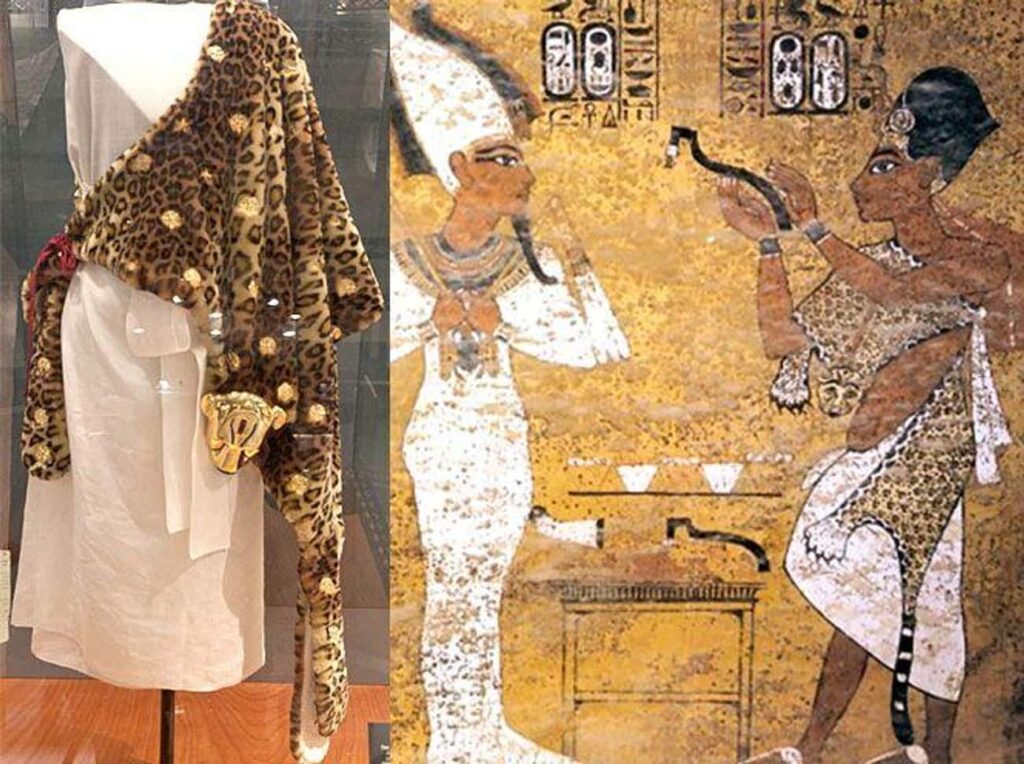

The Leopard Skin Robe

When Howard Carter found Tut’s priestly robe, the leopard skin was severely decayed, so only the golden head and embellishments survived. It was a garment reserved for the pharaoh – the high priest of all the gods and temples in the land – and his Sem priests, who wore it while performing funerary rituals. A painting from Tut’s burial chamber shows his successor, Ay, wearing a leopard robe while performing the “Opening of the Mouth” ceremony on Tut. In this ritual, Ay assumed the role of the God Horus and Tut the dead king Osiris. Ay became king by divine approval, and Tut, with his mouth “opened,” was allowed to eat and drink in the afterlife, ensuring the 36 jars of red wine and 48 meat mummies in his antechamber wouldn’t go to waste.

The Faux Leopard Cloak

The vegan leopard cloak was probably made for Tut right around the time that he was crowned pharaoh. There are cartouches just above the gold head that bear the king’s coronation name, and a Horus falcon stretches diagonally in the center. The embroidered stars in circles covering the fabric meant that it was worn at the funeral of someone important. possibly while performing the “Opening of the Mouth” ceremony on his father and predecessor, Akhenaten. Tut and his priests wore both real and fake skins for religious ceremonies.

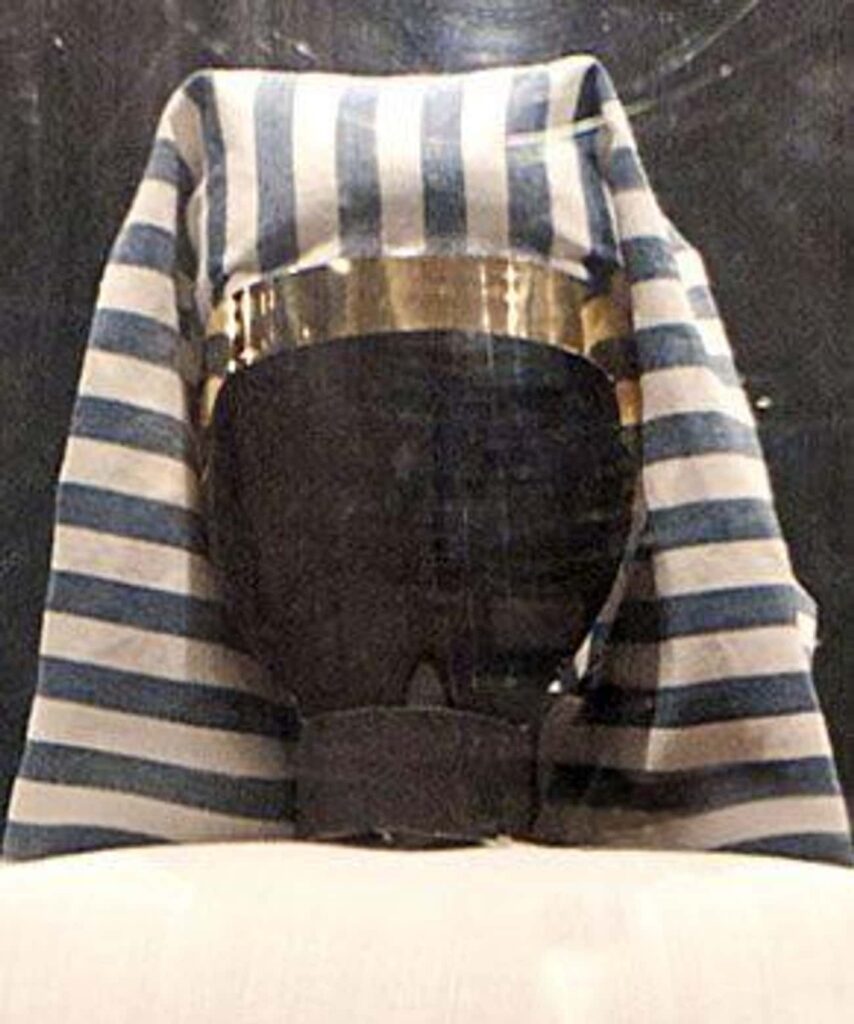

The Famous Pharaoh Hat

The nemes, the striped headdress is worn only by kings and gods and is one of the oldest fashion items in Ancient Egypt. It was usually held in place by a gold band across the forehead with a uraeus or cobra symbolizing divine authority and the Nekhbet vulture symbolizing the unification of Upper and Lower Egypt. Howard Carter made a note of Tut’s nemes describing it as “striated with lapis blue glass, much discoloured and decayed” and ended up tossing it in the trash.

The Mystery of the Wings

Tut’s wings were initially believed to be head pieces but then identified as upper armbands. Tut wore these falcon wings of Horus in pairs, one on each arm with a wing draped over his front and one over his back so that his chest was completely enfolded. The birds were constructed from individual pieces of red, blue, and white dyed linen sewn onto the base. Because the cuffs are extremely small, Tut either wore these wings when he was very young, or he had very skinny upper arms.

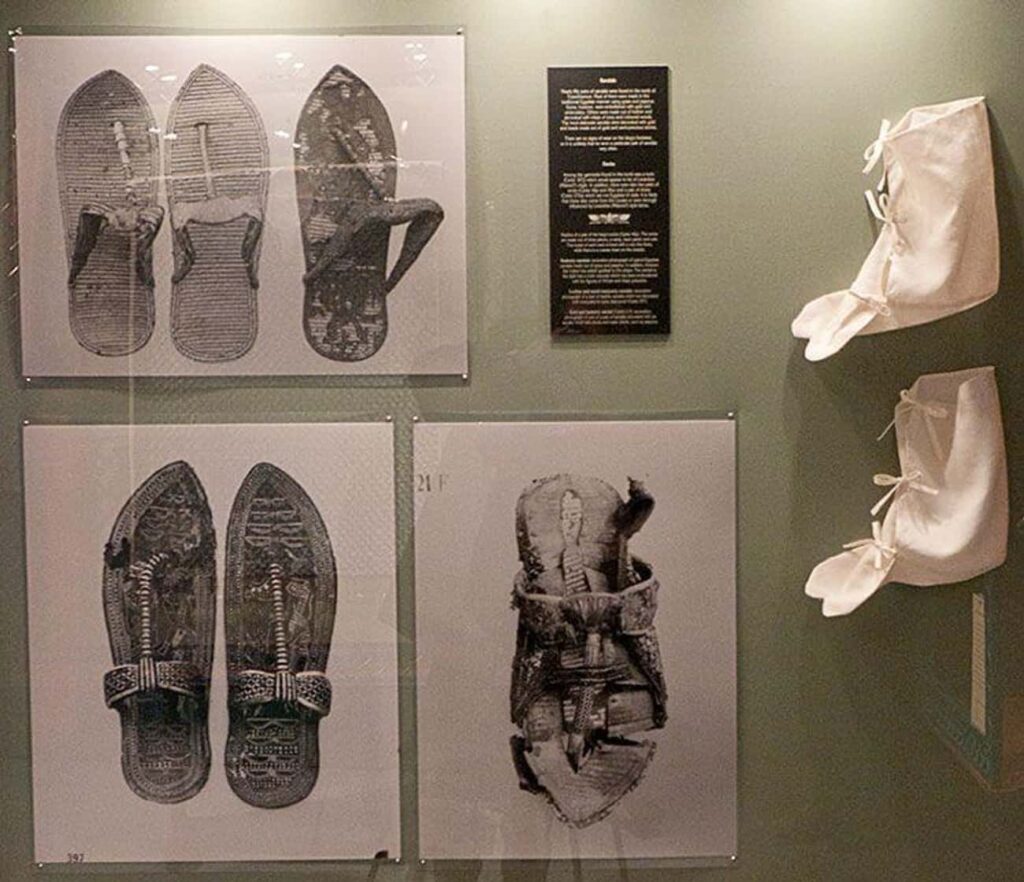

Ancient Socks

Tut’s socks were a surprise find for Howard Carter because there were no representations of anyone wearing socks in Ancient Egypt. Children were barefoot until the age of six, and after that, only wealthy Egyptians wore shoes that were usually made of vegetable materials. Tut’s socks are stitched together from several pieces of cloth with a gap between the two biggest toes to fit his sandals.

The royal Gloves

Tut was buried with 14 pairs of gloves. Several of the gloves were fingerless gauntlets designed for holding the reigns of his chariot. Made in fine linen with Lotus blossom patterns, they proved challenging to reconstruct.

The Pear-Shaped King

While reconstructing one of Tut’s loincloths, Dr. Vogelsang-Eastwood discovered that Tut’s measurements were roughly 31/ 28/ 43 inches.

For more fashion news CLICK HERE.